The Federal Reserve has basically one tool for trying to control the nation’s economy – the prime interest rate. The board members meet on a regular basis and taking the current inflation data, as well as “broader macroeconomic data,” into account, they use their collective judgement to decide whether to raise or lower the prime rate.

Let me develop an analogy. Think of the prime rate as being the setting on your home’s furnace (slightly unrealistic, since most furnaces are binary – either off or on – but let’s suppose we’ve got a control that lets us turn on the heat a little, or a lot – we can set the furnace anywhere from 0 to 100%). The inflation rate would correspond to a thermometer in your living room. Broader macroeconomic data might be things like what’s the outside air temperature, is it sunny or cloudy, is it windy? The fed has a target inflation rate of 2% — we have a target home temperature of say 70o F. Of course, most homes come equipped with a simple device (a thermostat) that automates things, but for the moment, let’s pretend that we’re controlling the furnace manually.

You’re in the furnace room and the family yells down at you: “Hey it’s 68o in the LR!” You figure you want to heat things up, so you set the furnace to 25%. A little while later the fam reports “Yo! it’s still 68o.” “What’s it like outside?” you ask. “It just started snowing!” they reply. This is you developing “judgement” – you now know that moving the prime rate by 25 basis points isn’t enough in a scenario where there are strong economic headwinds. So you crank it up to 75% and a little later they complain that they’re broiling and they’re going to open a window. “Don’t you dare!” you riposte, while flipping the furnace to OFF and running upstairs to prevent the introduction of arctic air to the homestead. I’m sure you can imagine more comedic consequences — it’s clear that despite your eventual attainment of complete and total “furnace control wisdom” this process is going to lead to the house temp constantly cycling between too hot and too cold…

Maybe we should install a thermostat.

But wait! There’s more… There’s a beautiful area of Math known as Control Theory (to be fair, it’s a topic that’s sort of shared between Electrical Engineering and Math). Control theorists have studied the devil out of thermostats, and there is an inescapable “hysteresis effect” — a fancy way of saying that the temperature will inevitably cycle between a little too cool and a little too warm. For controlling one’s home temperature the effect is almost too small to notice, but if we wanted to automate the Federal reserve’s function the hysteresis effect would be undesireably large. This is mostly about lag. The temperature in one’s home can be measured more-or-less instantaneously; the data that goes into the Fed’s decision making is as fresh as they can make it, but at least a month or so old. Besides the hysteresis issue, putting a thermostat on the U.S. economy would be ill-advised for a variety or reasons: good human judgement can be used to adjust our control inputs to take many ancillary factors into account – there is also a psychological component concerning how market participants react to Fed pronouncements.

I would like to advocate for the Fed hiring a good EE who could help them to tune a PID controller for the prime rate. The rest of this essay will be about explaining what a PID controller is, and why they are so awesome. I don’t at all think that human judgement should be taken out of the picture, but having a Control Theory recommendation as a basis for deciding about rate changes would have a lot of advantages. To be honest, people don’t get onto the Federal Reserve Board without being pretty smart, so it’s entirely possible they’re already taking the stuff I’m talking about here into account – which would make me writing about control theory relatively pointless, but I’m halfway into writing this thing at the moment so I’m just gonna keep rolling.

So. What is a PID controller? First, let me say they’re fairly ubiquitous – but the example most people will be familiar with is the cruise control in a car. Second, let me mention that they’re amazing! A properly tuned PID controller makes it look like some ethereal, invisible hand is just grabbing your system, moving it to the set-point and holding it there against its will. PID stands for Proportional, Integral, Differential – the three factors that the controller uses to decide how to adjust the control input. Okay, I seem to already be using some jargon, so I’d better be more up front: A control variable is something whose value we are interested in, uhmm, controlling (like room temperature, vehicle speed, or inflation rate). A control input is something (like furnace setting, gas pedal depression, or prime lending rate) that effects that control. A control system will also have a set point – a value for the control variable that we want to maintain (like 70o, 65mph, or 2%). So, let’s go through the P, the I and the D pieces in successive paragraphs.

P stands for proportional. This means the control input is changed in a way that’s proportional to the deviation of the control variable from the set point. That’s probably intuitively obvious — if the current temperature is far below the set point we should turn the furnace up more than if it is close. Please notice that this is a very different thing from changing the set point. If it’s cold in your house, turning the thermostat up to 90o won’t make it get warm any faster than setting it at 72o. (Although, if your thermostat was a PID controller, maybe it would…) This part of the behavior of automotive cruise control is why if you hit “resume” when your car is stopped and the CC is set for highway speed, the acceleration is pretty decisive — as compared to what happens when you’re only a few mph below the set-point when you hit “resume”.

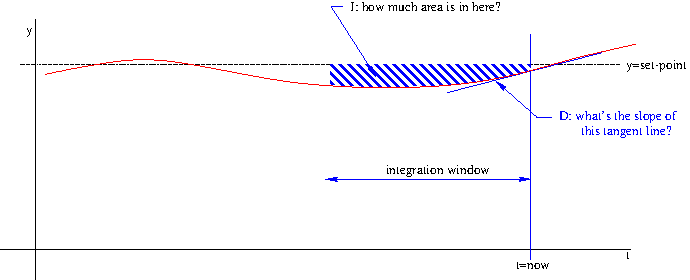

If you were driving on a long uphill section of road and the “gas” was applied only in a way that was proportional to how far your speed was below the desired speed, you’d end up cruising a few mph below what you asked for. This is where the I (integral) part of PID comes in. We give the control input a little extra kick when the control variable has been some distance away from the set point over a largish period of time.

Finally, on to D. Would you keep the gas pedal floored if you were going 63 mph and seeking to level out at 65mph? Probably not. In this final component of the PID trio, we look at the rate of change of the control variable. If your speedo reading is going up 1 mph every second, you should cut back on the control input (i.e., ease off the gas) so you don’t shoot right past the set-point and end up with a speeding ticket.

The last piece of the puzzle is this: how much should we weight the three components, P, I and D, in determining the control input? The physical nature of the system we’re controlling is going to influence these weights. For instance, a heavy car with a low-power engine will need to weight the I part more heavily than the D part. Conversely, a light, high-powered car can largely ignore the I part and concentrate on D. Figuring out the right weights to use to translate the P, I and D components into an actual setting for the control input is what I meant a few paragraphs back when I mentioned “tuning” a PID controller. This is really not Rocket Science, although, given how many PID controllers you’ll find on actual rockets, maybe it partly is Rocket Science…

There are a few other technical details – for instance, you have to decide on a time-frame to use in calculating the I part – but basically, you fiddle around with values for these 3 weights in a variety of scenarios until the control system responds the way you’d like it to. In a certain sense, translating experience with a control system into weight values for P, I and D is what is meant by the phrase “developing judgement.”